Shared Benefits of Protecting Fish Spawning Aggregations Lead to Cooperative Management

Location

Manus Province, Papua New Guinea

The challenge

The coral reefs of Papua New Guinea (PNG) are among the most species-diverse in the world and an important source of food and income for communities. The 40,000 km2 of coral reefs form an extensive resource that is exploited almost exclusively by small-scale artisanal and subsistence fishers. On a national level, harvests are thought to be well below the maximum sustainable yield. Despite the overall health of the PNG fishery, local over-exploitation has been noted, particularly in fisheries with access to cash markets. Fish spawning aggregations are particularly vulnerable even to light fishing pressure, which can have a profound impact on the reproductive population over a brief period and substantially reduce reproductive output.

Healthy hard coral reef with Anthias and Coral Grouper at Killibob’s Knob dive site in Kimbe Bay of Papua New Guinea. The Coral Triangle contains 75 percent of all known coral species, shelters 40 percent of the world’s reef fish species and provides for 126 million people. Photo © Jeff Yonover

As in many other tropical nations, fishery management in Papua New Guinea requires a community-based approach because small customary marine tenure (CMT) areas define the spatial scale of management. However, the fate of larvae originating from a fish spawning aggregation in a community’s CMT area is unknown, and thus the degree to which a community can expect their management actions to replenish the fisheries within their CMT is unclear. Therefore, information on larval dispersion is important: if larvae disperse in large numbers across tenure areas, this can provide a strong impetus for cooperative management between adjacent communities.

Actions taken

To better understand the dispersal dynamics of fish larvae, The Australian Research Council (ARC) and The Nature Conservancy (TNC) conducted a genetic analysis to measure larval dispersal from a single fish spawning aggregation (FSA) of squaretail coralgrouper (Plectropomus areolatus) at Manus, Papua New Guinea. In 2004, to replenish local fish stocks, fishers within a single CMT area established a marine protected area (MPA) protecting 13% of their fishing grounds, including the studied FSA. Researchers and local fishers sampled this FSA over 2 weeks in May 2010 and collected tissue samples from, and externally tagged, 416 adult coralgroupers, which represented an estimated 43% of the FSA population.

Conservancy marine scientist, Alison Green surveying coral during a rapid ecological assessment (REA) in the area of Manus Province, North Bismarck Sea, Papua New Guinea. The coral reefs of Papua New Guinea (PNG) are among the most species-diverse in the world and an important source of food and income for communities. Photo © Louise Goggin

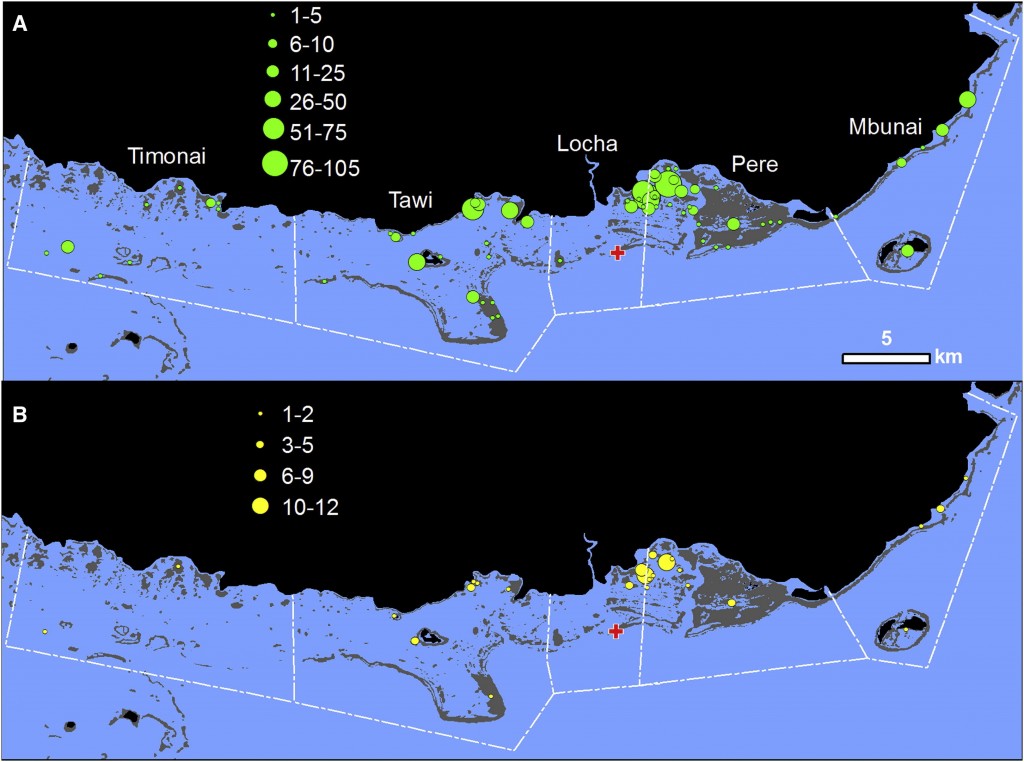

Over 6 weeks (November–December 2010), 782 juvenile coralgroupers from 66 reefs were collected from within the CMT area and four other surrounding CMT areas up to 33 km from the sampled FSA. The analysis identified 76 juveniles from 25 reefs that were the offspring of adults sampled at the FSA.

Researchers quantified how larvae dispersing from the coralgrouper FSA contribute to recruitment in the surrounding CMT area and four adjacent CMT areas. They found that 17–25% of recruitment to the CMT area that contains the sampled FSA came from that same FSA and that in each of the four adjacent CMT areas, 6–17% of recruitment was also from the sampled FSA. Finally, the dispersal models based on these data predict that 50% of larvae will settle within 13 km and 95% within 33 km of the FSA.

Location and abundance of sampled and assigned juveniles: spatial patterns of coral grouper (A) juvenile sample collection and (B) juvenile parentage assignments. Green (A) and yellow (B) circles are scaled to the number of juveniles. Adults were sampled from a single fish spawning aggregation (red cross), and juveniles were collected from 66 individual reefs (green circles in A). White dashed lines show the customary marine tenure boundaries of the five communities, with the name of each community in white (A). Land is black, coral reefs are gray, and water is blue (Almany et al. 2013).

How successful has it been?

The final results and recommendations of this study were presented in November 2011 to all five communities that participated in the research as well as in Mbuke, the largest community among the offshore islands to the south of the study area. The three main conclusions from this work are:

- Small, managed areas that protect FSAs can help rebuild and sustain a community’s coralgrouper fishery because many larvae stay close to the FSA.

- The coralgrouper fishery represents one large stock that would be better managed collectively because some larvae and fish travel across CMT boundaries.

- The results of the coralgrouper study are similar to results from other studies on both fishery and non-fishery species, all of which suggest that some larvae only travel short distances from their parents.

These results suggest that community-based management can definitely provide local benefits for some fishery species, and possibly for a wide range of fishery species.

At the time of the study, there was no formal framework in place to support collective management. Communities had traditionally made independent decisions about the fisheries within their CMT area. However, many community members immediately saw the value in collective community-based fisheries management after the results of this study were presented. Those communities in support of collective management, which consisted of eight Titan tribal areas including the five CMT areas that participated in the coralgrouper study, sent 70 leaders to a gathering in June 2013 to officially establish the Manus Endras Asi Resource Development Network.

The eight tribal areas of the network contain more than 10,000 people spread across approximately a third of Manus province (~73,000 km2 of ocean). The network was established around existing sociocultural boundaries, with all members sharing a common language (Titan), common religion (Wind Nation), and a maritime culture. Some strategies the network used for achieving its mission include: advocating for and supporting equitable and sustainable development to improve livelihoods; preservation of cultural heritage; developing a learning forum to share experiences among network members to build local capacity; improving communities’ resilience to climate change through community-based projects; supporting research partnerships between communities and scientists that benefit communities; and establishing a network of managed and protected areas.

Island fishing boats and children in the area of Manus Province, North Bismarck Sea, Papua New Guinea. Photo © Louise Goggin

Since its inception in June 2013, the network has crafted and signed an official charter establishing itself as a registered business, developed and agreed on a strategic plan, and established a formal relationship with the Papua New Guinea National Fisheries Authority (NFA) to coordinate fisheries management activities. A recent outcome of this link with NFA has been a pledge from NFA to provide shallow water fish aggregating devices (FADs) to each community in the network to reduce fishing pressure on reefs.

At the September 2014 network meeting, the Tribal Council of Chiefs, acting as representatives of their tribal areas, approved the establishment of a comprehensive system of managed and protected areas across the entire area under the network’s jurisdiction. The two main goals of this system of managed and protected areas are to ensure the sustainability of a range of fishery resources and to protect cultural heritage sites. Next steps include a participatory planning workshop to integrate community priorities and conservation targets, local knowledge, and scientific data into a comprehensive spatial management plan for the area.

Lessons learned and recommendations

- Increased cooperation between communities in managing their fisheries benefits both fish populations and communities.

- Actions taken by one community will influence its neighbors, and cooperation among communities in managing a fishery is likely to enhance both fisheries sustainability and the long-term persistence of fish meta-populations.

- The strength of connectivity between coral reefs will decline as the distance between them increases, and localized larvae dispersal is common in coral reef fishes.

- Resolving larval dispersal patterns and their relationship to recruitment may provide a compelling argument for cooperative management.

- Fisheries management decisions on the size and spacing of marine protected areas may provide benefits to a range of species simultaneously.

Funding summary

Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

The David and Lucile Packard Foundation

The Nature Conservancy’s Rodney Johnson/Katherine Ordway Stewardship Endowment

National Fish and Wildlife Foundation

Lead organizations

Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

The Nature Conservancy

Partners

James Cook University

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology

The University of Hawaii at Hilo

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Resources

Video: Larval dispersal and its influence on fisheries management

Dispersal of Grouper Larvae Drives Local Resource Sharing in a Coral Reef Fishery